Prasat Thom temple complex in Koh Ker |

|

As already mentioned on the overview page, the principal structure at Koh Ker is called Prasat Thom. Most parts of it had been buiIt already before Koh Ker became the capital.

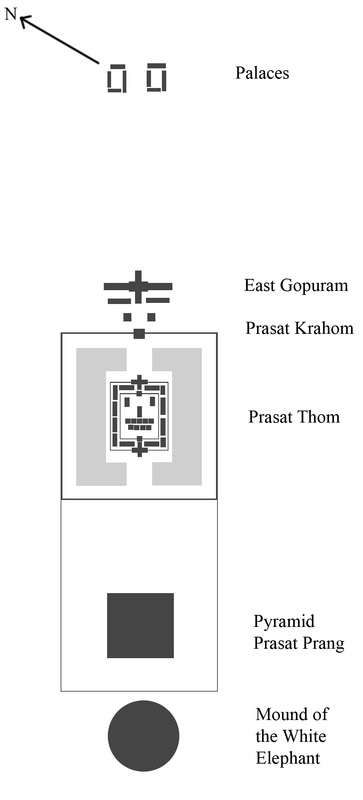

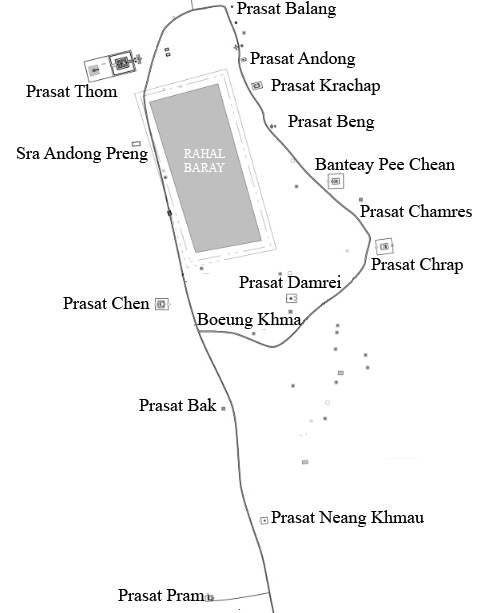

When Jayavarman IV established Koh Ker as his residence, he seems to have deposited an image or a symbol of the highest god, the Devaraja, on the pyramid in the rear or Prasat Thom. Coedès came to the conclusion that the pyramid and the Prasat were begun already in 921. Barth, based on his anlysis of the inscriptions of Koh Ker, even dated the beginnings of Prasat Thom back to 919. The royal temple proper, called Prasat Thom, is located to the north-west of Koh Ker's large central reservoir Rahal Baray. The main temple of Koh Ker is arranged along a prestigious procession way on a east-west axis (not exactly), leading to the step pyramid called Prasat Prang. The whole complex consists of two rectangular enclosures, joined end to end, and surrounded by a laterite wall. The front rectangle circumscribes a moat and on its island two smaller enclosures. This ensemble is Prasat Thom in a narrow sense. The rear rectangle contains the pyramid usually called Prasat Prang. In other words: The ground plan of the whole complex is not the usual concentric one, it is an elongated linear layout. This means, the compounds are located one after another, outer courtyards do not surround the inner ones completely. Parts of this layout (with the exception of the step pyramid) were copied by the famous and most beautiful Khmer temple, Banteay Srei, which is only a few decades younger. So the alley crosses different compounds, the most important is called Prasat Thom in a narrow sense, (thus not including the temple mountain Prasat Prang, which belongs to an adjoining compound). The kernel of Prasat Thom is an ensemble of nine Prasat towers surrounded by three enclosures. A ring of elongated buildings called libraries surrounds the core area between the first (inner) and second enclosure, an impressive moat between the second and third (exterior) enclosure walls. Thus, the whole complex (Prasat Thom in a wider sense) is a linear temple, whereas its central and largest compound (Prasat Thom in a narrow sense) is a concentric temple at the same time. The use of concentric enclosures with Gopuram gateways, introduced and prominent at Roluos, was renewed at Prasat Thom and some other sanctuaries in Koh Ker, but not at the terraced pyramid Prasat Prang. All in all Prasat Thom (as well as Banteay Srei later on) must be described as a combination of both linear and concentric layout. This combination of linear and concentric layout and many more details of the Prasat Thom complex were half a century later on copied by the architect of the most beautifully decorated, though much smaller temple of Banteay Srey. With the exception of Prasat Thom and Banteay Srei, axial linear ground plans were used in historical Khmer architecture only for temples situated at slopes of natural hills. Best examples are Preah Vihear at the Thai border and Wat Phu in today’s southern Laos. Let’s have a look to the groups of edifices aligned along the east-west axis in some more detail: Approaching it from the east, 15 degree north, to which direction it is oriented, this monument consists of - two buildings of the type called palaces, some 170 metres in front and on either side of the axis of the monument - ruins of a large gopura in front of the temple with adjoining galleries, possibly indicating a fourth enclosure - Prasat Kraham containing the largest room of the whole ensemble, is the third enclosure’s eastern gateway, a so-called Gopuram - the central monument, Prasat Thom in a narrow sense, is surrounded by a wide moat - Prasat Prang, the well proportioned step pyramid, is the landmark of Koh Ker - the ”tomb of the white elephant”, though less striking, is another artificicial hill |

Palaces at Prasat Thom

|

courtyard in the southern palace

|

The two groups called palaces of Prasat Thom are located on the opposite eastern side of the car park at Ta Prohm. They flank the beginning of the procession alley which is the axis of the whole complex. Despite their name, it is unlikely they really served as palaces. They are too small for this purpose and residential buildings of Khmer kings have been built of wood till the present day. The real Royal Palace of Koh Ker should have been a separate structure within the walled city but independent of the main temple.

However, the term “palaces” is used for those buildings in Khmer architecture that surround a shared courtyard and form a kind of cloister. For example, palaces are known as satellite buildings of the huge complex of Preah Vihear. They may have served as a room of contemplation for the royal family or a kind of reception for other guests of honour when state ceremonies were celebrated. The two so-called palace buildings at Prasat Thom in Koh Ker are the earliest found in Khmer architecture. The laterite buildings are believed to be contemporary with the oldest parts of Prasat Thom, this means, they are from about 920, when Koh Ker was not yet the capital. Each of this palaces consists of four long rectangular galleries with angular roofs and gables . They surrounding a rectangular court which, however, they are not built symmetrically and do not completely enclose it. Each gallery is divided into three sections of different sizes, some have porches, each supported by two rows of square stone pillars. The rooms are lighted by windows with balusters. The edifices perpendicular to the road are lighted on the east and those parallel to it on the south. The eastern pair, considered to have been a kind of halls of honour, is separated from the others by a wider space. Each has a porch facing that of the other across the road. The southern galleries have porches at both ends. The northern and western have no porches. |

Eastern Gopuram

|

The first building close to the car park is a huge gateway, a typical cruciform Gopuram with equilateral wings. It is lighted on both sides by large windows with balusters. The superstructure is missing.

It may have been the gate of a fourth (outer) enclosure originally planned and not completed or only built of perishable materials similar to the exterior enclosure of Banteay Srei. The lateral wings are joined by long galleries, which are closed on the exterior side and open towards the temple. Probably, the roofs consisted of bricks on wooden beams. They were supported on that side by round stone pillars. In the axis of the monument, the Gopura is followed by open portico galleries, which are supported by heavy square stone pillars, too. Two large asymmetrical laterite towers stood between them and the outer enclosure of the monument, one on each side of the entrance. |

Prasat Krahom, Gopuram of Prasat Thom

|

Prasat Krahom with lion guardian sculpture

Prasat Krahom at Prasat Thom, pedestal of a statue once depicting a dancing Shiva

|

Prasat Krahom (or Prasat Kraham) means "Red Temple", because it is built of red brickstone. It may have been reconstructed and enlarged after King Jayavarman IV had assumed the supreme throne and made Koh Ker the new capital. Parmentier even suggested that it may be later than the central sanctuary.

Prasat Krahom is the eastern gateway of the third enclosure of Prasat Thom, but sometimes regarded as a temple on its own, for two reasons. Firstly, Prasat Krahom is located outside the temple moat of Prasat Thom, and Prasat Thom in a very narrow sense is only the temple on that artificial island surrounded by that moat. Secondly, the sandstone tower of Prasat Krahom is taller than the Prasats in the centre of Prasat Thom. Indeed, Prasat Krahom contains the largest room of a sanctuary in the entire main temple complex of Koh Ker. Prasat Krahom, though a Gopuram, is built as a typical brick Prasat with with a square base and four retreating storeys and with sandstone doors and lintels. The scenes on the lintels seem to be mostly Vishnuite. The large western lintel is decorated with the figure of two warriors flanking an elephant. Unlike contemporary real Prasats, Prasat Krahom can be crossed because of doors to different directions. This is all the more remarkable as there are no earlier examples of Gopurams (gateways) in the form and size of Prasats in Khmer architecture. Thus, Prasat Krahom marks the beginning of the tendency to build towers as gateways, which became typical in later periods of Khmer architecture. Prasat Krahom is a prototype of Khmer gate towers in another respect, too. It sheltered statues, which became common in gateway towers later on. Fragments of a giant Shiva statue (Sadashiva) were discovered inside Prasat Krahom, its hands are exhibited in the National Museum in Phnom Penh now. This huge dancing Shiva had five heads and eight arms, traces of five of them were found. They carried attributes of a warrior. The whole statue was 3 or even 4 m high. It is the only known colossal sculpture of a dancing Shiva in Khmer art. Due to its size it was necessary to construct the surrounding building Prasat Krahom after the sculpture had been erected. As already mentioned, it was found shattered. More than tenthousand pieces were discovered. But most parts are missing. There are traces of looting in Prasat Krahom such as chisel tracks. This is why there are so many splinters now. When they were removed for research in Siem Reap and in Heidelberg, Germany, the local community of the village Koh Ker had to be involved to give permission and to hold a ceremony in order to appease the guardian spirit of the sculpture of Prasat Krahom. This chthonic spirit called Neak Thau is believed to live in the pedestal. There were four more statues in Prasat Krahom, one of them is now saved and exhibited in the Guimet Museum in Paris. Two sculptures depicted male drummers, the other two females, namely Uma and Kali. The latter had skulls and bones in her hands. Furthermore, there was a peculiar genie with animal heads. Prasat Krahom was once known for its carved lions, too. They flanked partition walls and stairways, but almost none of them remained in situ. Prasat Krahom had seated as well as lying and standing lions. Lying and standing lion statues are otherwise unknown in Khmer sculptural art. The alley mentioned above crosses Prasat Krahom and leads across the dam. The core temple of Prasat Thom is reached by a Naga-flanked causeway. |

Prasat Thom island temple

|

Prasat Thom moat between third and second enclosure wall

Prasat Thom inner (first) enclosure wall

Prasat Thom central nine Prasat towers

Prasat Thom central sanctuary

|

The kernel of Koh Ker’s linear main temple complex shows a quite common scheme of three concentric enclosures, as already mentioned. This concentric ensemble or at least the two enclosures surrounded by the moat are called Prasat Thom in a narrow sense.

There are several inscriptions engraved on the walls of the gateways. The most relevant is that on the first eastern Gopura (K.184) indicating that in 921 the temple was dedicated to a deity named Tribhuvaneshvara. The Sanskrit inscriptions also mention the consecration of a Shiva-Lingam for this "Three World's Lord". This means, the symbol of supreme royal power was erected already before Jayavarman IV ascended the throne and Koh Ker became the capital in 928. Furthermore, guardian spirits of his kingdom had already been worshipped at the core temple of Prasat Thom, before Jayavarman IV. became the king of the Angkorian Khmer empire. So only the first (inner) and the second enclosure walls are on the artificial island, the second enclosure wall runs along the wide moat, which in turn is surrounded by the third (exterior) enclosure wall. Between the third and second enclosure, the above mentioned eastern causeway over the inner moat as well as the western causeway leading to the pyramid were flanked by huge seven-headed Nagas on each side. The four Nagas are facing outwards, their tails are slightly lifted at the inner ends of the causeways. Behind each Naga is a giant Garuda sculpture, it seems to be depicted in its mytholifical act of pursuing the Naga. This thre-dimensionalensemble is one of the first appearances of the motif Garuda clinging Nagas, which will become an important sujet in later Khmer art. But it is a rare example of Garuda an Naga appearing separated. The second enclosure wall, which is of laterite, too, has two Gopurams of the usual type at the east and west. They are much smaller than Prasat Krahom, the Gopuram of the (outer) third enclosure. A row of narrow laterite buildings between the second and first (inner) enclosure form a kind of gallery ring similar to those at Pre Rup in Angkor one genration later on. At earlier temples such as Bakong in Roluos and Bakheng in Angkor and Phnom Krom near the Tonle Sap, there were only hints of what becomes now an almost continuous series of galleries between the first and second enclosures of Prasat Thom. The first (innermost) enclosure is built of sandstone. In this inner courtyard are two library buildings. They are the first Khmer libraries with a rectangular instead of a strict square ground plan. As usual, they are opened towards the main sanctuary, in this case towards the west. Within this inner enclosure there are also twelve more ruins of small towers surrounding the central sanctury, arranged in griups of three at each corner of this inner courtyard. All of them are built of brick with sandstone lintels and colonnettes. All 21 Prasats seem to have housed Lingas. The core structure of Prasat Thom, in the very centre, are nine towers arranged in 2 rows of five and four on a single t-shaped platform. Though the kernel of the whole huge complex, they are of modest size and built of brick, too. An elongated building in the main axis, in front of the central Prasats and on the same platform, is an early example of a typical antechamber called Mandapa in Indien architectures. In Hindu temples Mandapas are the places of worship, where prayers are held and donations for the gods are handed over to the Brahmin priests. The core sanctuary (the sanctum surmounted by a Shikhara tower in India or a Prasat tower in Cambodia) was reserved for the idol if the divinity. Some fragments of a bull or buffalo can still be observed in situ. Usually the animal sculpture is thought to depict Nandi, Shiva’s mount. This interpretation was proposed by the French Angkor-discoverer Louis Delaporte, who explored Koh Ker in 1885. There are two Shiva symbols in front and behind Prasat Thom, namely the dancing Shiva in Prasat Krahom and the Linga on top of Prasat Prang and the 21 Lingas in all Prasats of the inner enclosure. Thus, it appeared likely that figures in the central part of Prasat Thom were Shivait, too. However, new research came to a different conclusion. Now it is pretty sure that this sculpture is a buffalo and not a bull. One reason for this new interpretion is the angle of the horn. In Hindu mythology the buffalo is the mount of another god, not of Shiva but of Yama. Yama is the god of death or more precisely: the god of judgement over the deceaced. The buffalo belonged to a group of sculptures with Yama in the very centre. The whole group depicted the judegment over deceaced. Figures usually accompanying Yama are the writer Chitragupta, a hunchbacked with a pair of scales of justice and the personification of punishing cane Dhanda. The group in the main hall of the inner enclosure interpreted as Yama’s judgement offers a clue to a completely new or additional second interpretation of the whole group. It was not only a Shiva-temple as a symbol for supreme power. It was also a temple dedicated to Shiva as the renewer of life. The central Lingam in the middle of the inner enclosure and the largest Lingam at the top of the pyramid were only reached after passing Yama’s judgement. And the dancing Shiva in the entrance gate of the third enclosure, Prasat Krahom, is a symbol of the laws and regularities and the power of time, too. So the spacial journey through the temple is a journey through time, too, and its final stage is reached only after death and judgement. This interpretation means a second way of honouring the king, not only for his power, but also for his higher postmortal state, then even closer to Shiva. To come to a conclusion: The Yama-interpretation of the main group of sculptures in Prasat Thom means, that this was not only a state temple, but a sepulcral sanctuary, too, glorifying the dead king who passed the judgement. It is very likely - and better known - that Angkor Wat was was not only a state temple, but the tomb for the king who built it. And the judgement of Yama is a main motif at the famous galleries of the Angkor Wat. The new interpretation of the central group of Prasat Thom in Koh Ker gives a hint that Angkor Wat - as a state temple and a tomb at the same time - may not have been the exemption from the rule, but that also earlier state temples already served for glorifying the deceaced and not only the living king. Local tradition regarded Pre Rup in Angkor, only few decades younger than Prasat Thom in Koh Ker, as a royal burial place, and maybe there is more truth in it than expected and state temples in general were also built for commemmorating the dead king and his increased power after he is reborn and juged to be dignified to live closer to the gods. The procession along the temple axis may also have been a symbolic ritual for rebirth and passing Yama’s exame for visitors. But visitors of Khmer state temples were not common people but only dignitaries, members of the royal and priestly families. When leaving the core temple of Prasat Thom westwards, there will be another hint that this main temple group had a burial function, too, namely the so-called tomb of the white elephant behinf the pyramid. A famous sculpture depicting two wrestlers was discovered in the western part of this core structure of Prasat Thom. They are now displayed in the National Museum in Phnom Penh as a perfect example of the dynamic style of Koh Ker. The western Gopuram of the second enclosure sheltered a big sculpture depicting Shiva and his consort Uma riding on his bull Nandi. Several inscriptions in Sanskrit and Khmer, more or less decipherable, were discovered at Prasat Thom, most of them on the walls and pillars of the Gopurams. |

Prasat Prang at Prasat Thom

|

Prasat Prang step pyramid at Prasat Thom

|

The procession alley crossing Prasat Thom ends at Koh Ker´s landmark, the step pyramid. It is surrounded by its own enclosure, but only a single one, integrated into the linear layout of Prasat Thom.

The artificial temple mountain dressed in sandstone is 62 m wide and 36 m high, , compared with 15 metres for the Bakong. The pyramid has seven terraces of regular hight, they are well proportioned, their edges form the linear outline of an almost equilateral triangle, taller and more slender than the previous pyramidic state temples Bakong in Roluos and Bakheng in Angkor. Prasat Prang`s shape come closest to the appearance of some Mesoamerican step pyramids of the Maya. On the south side, the sixth step has a recessed false door. The uppermost terrace measures 12 metres on a side. The pyramid’s only stairway is on the eastern side. There is no Prasat tower on the top now, making the pyramidal outline all the more emphasized. Maybe a temple tower on the very top, similar to that of Bakong, was planned and not completed in time or it was of perishable materials such as timber instead of stone or the only monument on top was the Lingam that in this case was intended to be visible. In case a Prasat has been built on top to shelter the Linga,, the extreme point of this pyramid probably reached the height of 64 metres, which is also the width on ground level. It would have been of equal height as Angkor Wat. The last two terraces may be considered as the basement of this Lingam, which is not preserved, only its pedestal supported by life-size lions remained.. However, it is probable that this pyramid carried the Linga Tribhuvaneshvara, which was King Jayavarman IV's state idol. Not even traces of this Linga have been found, it may have been made of metal, gold or gilded bronze and may have been looted. But on the basis of the huge size of the pedestal at the top of the pyramid, Parmentier estimated that this Lingam’s dimensions were 4.50 m in height and 1.50 m in width, if modelled in the usual three-stage form square at the base( symbolizing Brahma), octagonal in the middle (Vishnu) and cylindrical and phallic at the top (Shiva). If this Linga was made of sandstone, its weight would have been more than 24 tons if built of sandstone and much more if adorned with metals. At least 400 men, aided by elephants, were required to lift it on the pyramid. The erection of this Linga is praised in several inscriptions. The technical tour de force explains the boasting mood at the start of the inscription K.824: “Fortune, success, happiness, victory.” An inscription at Prasat Damrei mentions that a huge Lingam was erected on top of a Prang. One of the Sanskrit inscriptions of Prasat Thom, dated 921, mentions the erection of the god Tribhuvaneshvara by Jayavarman IV. Another, in Khmer, of the same date, describes the donations of two dignitaries to the Devaraja (in Khmer: Kamrateng Jagat ta Raja). It is pretty sure that the Lingam and the deity Tribhuvaneshwara are to be identified. However, there is some debate if the idol of the “Godking” Devaraja, which is reported to have been transported to Koh Ker, is this very same Lingam. But usually the main shrine on top of a Khmer temple pyramid sheltered only a Lingam and no figurative idols and were a place of worship for the Devaraja. So usually Devaraja image and Tribhuvaneshvara Lingam are identified in the case of Koh Ker. |

Mound of the White Elephant

|

There is another structure belonging to the main complex of Koh Ker. Behind the rectangular enclosure of the pyramid’s compound is a conical mound completely overgrown and appearing natural, but actually it is artificial. Locals call it the tomb of the white elephant. White elephants are symbols of royal power in Southeast-Asia. Usually modern Khmer names for ancient structures rarely offer any clues about their historical purpose or meaning, but in this case the modern interpretation could make sense. There is some connection between this second temple mountain and the historic King Jayavarman IV, maybe it even served as his tomb.

However, Parmentier thought the mound might have been a provisional abode of the Devaraja, where this royal idol could have rested before the pyramid was built. But it could be the other way around: The second temple mound could have been a later addition which was never completed. There is a small path leading to the top, but for security reasons it is closed. |